Chapters

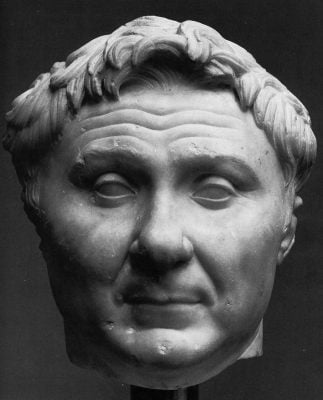

Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (“the Great”) was born on 29 September 106 BCE as Gnaeus Pompeius. He received his nickname Magnus from his contemporaries because of his great political and military successes and his services to Rome. Roman commander and politician; son of Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo.

Youth

Pompey was born in a senatorial family. He gained his first military and political experience under the guidance of his father Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, who was a consul in 89 BCE. Under his command, he took part in the Social War. In 87 BCE, when Pompey was 19, his father died, leaving him his fortune and the good name of the family.

After Sulla’s troops got to Brundisium (today’s Brindisi) in 83 BCE, he joined him with his three legions, which he managed to form near Picenum. Over time, he became Sulla’s personal proponent as he owed him the command without an initial period of office.

Military career

In 82 BCE he took part in the conquest of Rome, and then, thanks to Sulla, he took command of units fighting with Marius‘ supporters in Sicily and in Africa. In 81 BCE he eventually defeated the army of the Populares.

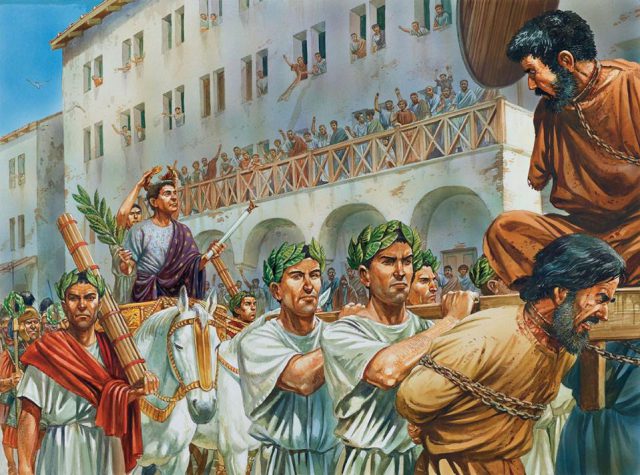

After the victory, he received the title of ‘Great’ (Magnus) from Sulla and, with his consent, he triumphed in Rome. Only in 78 BCE against Sulla’s will, he supported the candidacy of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus for the consulship, which inflamed his relationship with the dictator. However, when Lepidus attempted to overthrow the Sulilian regime, Pompey protested against him. This contributed to the defeat of Lepidus and strengthened Pompey’s position in Rome.

In 77 BCE Pompey stood at the head of the troops fighting with the Marian supporters in Spain, led by Sertorius. After Sertorius’ death, as a result of a conspiracy, and the final defeat of the opponent’s troops, Pompey returned to Italy and took part in the fight against Spartacus’ troops in 71 BCE.

Together with Marcus Crassus, with the consent of the Senate, they took over the consulship in 70 BCE. Pompey became a consul, even though he did not reach the legal age and had not previously served other offices required by the so-called cursus honorum. The new consuls cancelled the most restrictive part of the laws introduced during Sulla’s dictatorship, restoring, among others, tribal power.

In 67 BCE he received special privileges in the Mediterranean, thanks to which he carried out a quick, victorious campaign against the pirates.

Thanks to the intercession of Caesar and Cicero, Pompey undertook the war against Mithridates VI of Pontus. Taking advantage of Lucullus‘ previous successes in 74 BCE, he won and in 66 BCE he eventually defeated Mithridates’ army, imposing Roman authority. Then Pompey connected Pontus with the province of Bithynia in 65 BCE.

Pompey continued his campaign in Asia Minor by occupying Syria in 64 BCE and thus putting an end to the rule of the Seleucids. He entered Judea, capturing Jerusalem in 63 BCE. He created a new Roman province of Syria from the occupied territories. He created the entire system of politically and financially dependent countries from Rome, which Cappadocia, Armenia and the Bosporan Kingdom were included. It can be said that in the years 66-62 BCE Pompey was the actual master of the Roman Empire.

After settling matters in the East, in 62 BCE he returned to Rome, where he triumphed. However, the Senate, fearing the increasing authority of Pompey, refused to approve his orders in the East and give land to veterans.

First Triumvirate

Thus in 60 BCE Pompey entered into an agreement with Crassus and Caesar, creating an informal First Triumvirate, providing all three with real power over the state, which allowed Pompey to force his demands. In 56 BCE the triumvirs renewed the agreement in Lucca, and Pompey received the governorship in Hispania.

In 55 BCE he was a consul along with Crassus for the second time. In the same year, in order to win the endorsement of the people, he built the first stone theatre, the so-called Pompey’s theatre. After the death of Crassus in the battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE, there was a break of the triumvirate and a conflict occurred between Pompey and Caesar. In 52 BCE in the face of a wave of riots caused by the struggle of Milo and Clodius, he was elected a consul without a colleague in the office (sine collegae). He later led the election for the last five months as consul of his father-in-law, Metellus Scipio.

According to some sources, Caesar was supposed to mourn his rival and pay his corpse great respect and put a kiss on his forehead.

Civil War

Presumably, on 10 January 49 BCE, 53-year-old Caesar, crossing the border of Italy on the River Rubicon, began a conflict with Pompey, which turned into open war. The Senate recognized Pompey as the defender of Rome and granted him a lot of powers. Not having enough strength to oppose the legions of Caesar in Italy, Pompey got to Greece, where he managed to gather a large army.

Detailed description of the Civil War

The conflict between Julius Caesar and Pompey was to decide about Rome’s future.

After his victory at Dyrrachium, which he did not use, a month later, on 9 August 48 BCE, there was a battle of Pharsalus in Thessaly. Pompey’s army suffered a devastating defeat in spite of the military advantage. The defeated commander escaped to Egypt.

Evacuation to Egypt

On 28 September 48 BCE Pompey’s messengers came to Egypt. They had an audience with a ten-year-old Ptolemy XIII, for whom his guardians and advisers: Potheinus, Achillas and Theodotusreally ruled. They obtained assurance that their leader would be accepted in Egypt with appropriate honours. Pompey did not have to be afraid of anything, because it had been him who in the year 55 BCE had restored the throne of the pharaohs, the father of the present ruler – Ptolemy XII Auletes. In Egypt still stationed Roman legions consisting largely of Pompey’s former legionaries, still from the times of the fighting with Mithridates VI. Pompey was the guardian of the royal family appointed by the Senate.

The situation, however, was not so simple. At that time in Egypt, there was a civil war between supporters of the minor Ptolemy XIII, and supporters of his sister, then twenty-one-year-old Cleopatra. The siblings were to rule together, according to the wishes of their father, who died in 51 BCE. However, a fight quickly took place between them. Cleopatra was banished from Egypt in April of 48 BCE, but quickly gathered an army in Syria and struck Egypt. Both armies met in the area of the Pelusium fortress, in the east of the country. However, the battle did not take place. Ptolemy’s supporters realized that supporting defeated Pompey in such conditions would result in Caesar’s immediate support for Cleopatra. Finally, the discussion about how to deal with Pompey was interrupted by Theodotus saying “the dead do not bite”.

Meanwhile, Pompey managed to leave Thessaly and get to the island of Lesbos. He took his wife Cornelia and son Sextus from there. He then sailed along the shores of Asia Minor to Cyprus. Along the way, he collected his own soldiers who had survived and some of the slaves, of which he also created troops (numbering c. 2 000 people). They sailed in the direction of Alexandria, from where they were directed to Pelusium. Then, Achillas went to Pompey’s ship on the small boat. Two former Pompey’s officers were with him – Septimius and Savius. Many of the Pompeians present on the ship advised Pompey to sail away, as the scorn he was experiencing with such modest welcome spoke for itself. Septimius, however, from the boat, greeted Pompey like an emperor, and then Achillas began to speak in Greek. He explained that the larger ships would not get through shoal the, but it was noticed that Egyptian soldiers were embarking nearby ships. Nevertheless, Pompey decided to get on the boat. Along with him, there were also two officers, the freedman Pompey named Philip and one slave. Pompey turned to his wife and son and said in Greek: “Whoever enters the tyrant’s house is his slave, even if he has come free.” There was silence on the boat, only Pompey tried to start a conversation with Septimius, but he did not reply, only nodded. As they approached the shore, Pompey rose and leaned over to Philip’s hand as he suddenly felt a strong stabbing punch. It was Septimius who had stabbed him with his sword, others had their swords drawn, and Pompey fell bloodstained, and tried to cover his face with his toga.

Septimius carried the severed head of his former commander to king Ptolemy. Then on 28 September, there was the thirteenth anniversary of Pompey’s second triumph in Rome. Pompey’s body lay on the beach until dusk, then his freedman Philip, washed it and wrapped it in his own tunic. Then he arranged a small funeral pile and set fire to his master’s body. Then came an old man who had once served under the orders of Pompey in Spain. Only the two of them stood by the burning body of Pompey the Great, the Roman conqueror, the first Roman who had entered the Temple in Jerusalem, he was supposed to have slipped on its steps. He destroyed the kingdom of the Seleucids, existing for almost three centuries. He commanded the last and victorious battle against Spartacus, ending the uprising in Italy. Finally, he tamed pirates in the Mediterranean, who were its plague as they had been kidnapping free inhabitants of coastal lands and selling them into captivity, especially young women and children. Pompey put an end to that, and eventually, himself ended up as a villain.

Death

Pompey died on 28 September 48 BCE cut with the swords of his officers. People on the ship, seeing what was happening, quickly sailed away.

On 2 October Caesar arrived in Alexandria. Theodotus went for a meeting with him, carrying Pompey’s head and his ring. Caesar, seeing the head of the rival, exploded with anger, ordered Theodotus to leave his ship immediately, and he cried himself and gave honour to the deceased, then ordered to build a proper monument. Pompey’s fortune after his death was estimated at seven hundred million sesterces.

Marriage and offspring |

|